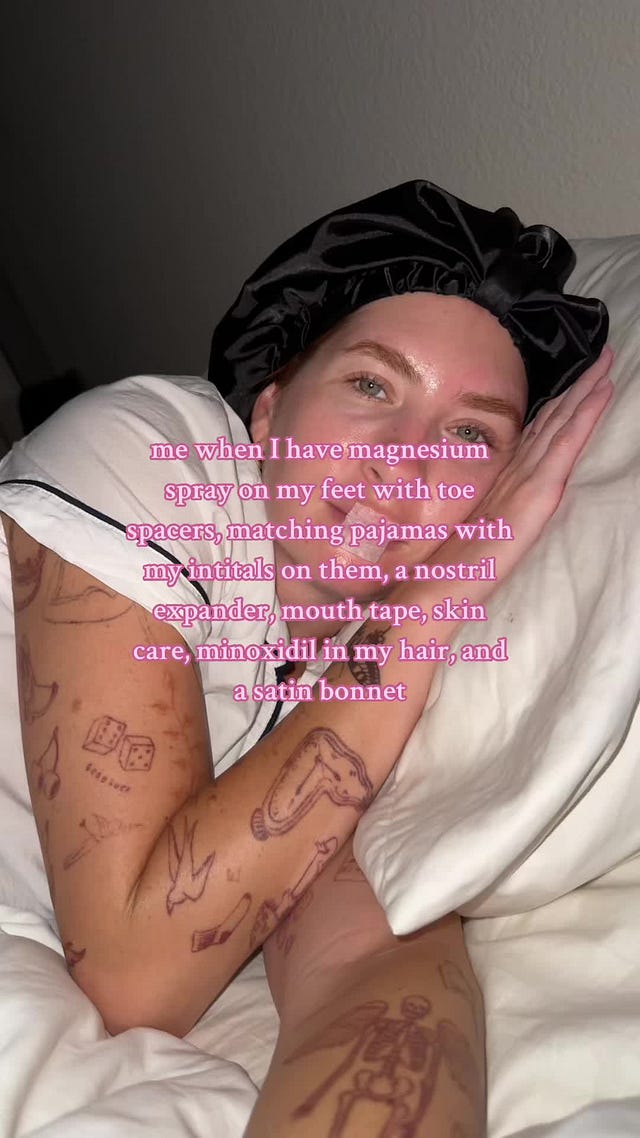

Only adding to my theory that TikTok only serves me content it knows will provoke me, I’ve recently been getting this onslaught of ‘morning shed’ routines. I watch video after video of dew-faced women undoing their chin strap, untaping their mouths and unfurling their velcro curlers. Like a caterpillar crawling from a cocoon, they awake to shed off layer after layer of self-care apparatuses, only to reveal their best selves.

It’s positioned like a hack – they’ve converted sleep into a time of passive self-optimisation. The rest of us had been wasting eight or so hours when we could have been maximising that time through steps and steps of products and rituals. The morning sheds remind us to play both harder and smarter.

But it feels like we’ve plunged into an ocean of absurdity. As if the patriarchy is negging us to see how far we will go for its approval. Because we look like clowns.

The culture of morning shreds tells us that it isn’t enough to starve or slave. Now we must sleep with our chins strapped and mouths taped (and at risk of choking in our sleep no less). We should fear our body’s biology – be wary of certain ways the body breathes and bloats. We should try and deprogram even our most human functions.

Hundreds and thousands of viewers watch captivated by these women and maybe out of a genuine curiousity. Young women watch with the Amazon app open in another tab, ready to buy whatever products they recommend – and all in hope of looking like the girl on the screen (I am said girl). Or at least, finding the same degree of control she seems to have over her life and image.

You have to wonder though when it bleeds into some sadomasochism. We have spent decades worried about the oversatuation of certain images of women on our TV screens (ie. the walking wounded) and surely, the algorithmically-prescribed images of women tethered to their bathroom sinks could be concerning. This isn’t an accusation of vanity, I’m just making the obvious comparison between the pre-shed attire and some sort of trauma room patient.

Barbara Ehrenreich said “In the traditions of Western thought, man represents wholeness, strength and health. Woman is a misbegotten man.” And it feels like there’s a tinge of misbegotten simmering beneath these images of women completing their morning shed routines – stomachs bandaged, faces strapped and mouths taped.

Is it too purple prose to say: their bodies healing the wounds that come with womanhood?

Femininity here feels like a spectacle. Historically, we’ve so rarely known women’s inner lives and now, so many of the images we see of them alone in private are them embalmed like they’re recovering from a wound.

No doubt, some part of this ritual makes these participants feel good. Control feels good. Being closer to the possibilities that come with possessing a snatched, ageless face feels good. Not having to try and do your hair in the morning, feels good. I mean, beauty is pain.

But does it hurt?

A TikTok I watched this morning haunts me. It was a woman putting hair ties around the base of her ears for ‘lymphatic drainage’ – as she winds the bands, she complains “It does turn my ears a bit red and blue.” When asked in the comments if it hurt, she said “Not no, but not yes.”

It reminds me of this part in The Beauty Myth by an author who shall not be named: “For as far back as women could remember, something had hurt about being female*.” As described in said book, pain can trickle into every part of one’s day as the patriarchy demands our discomfort even at home. Or apparently, even when you’re unconscious.

Maybe the women who sleep in the shed-able apparatus are champion sleepers, unaffected by all of the gear encasing their bodies. But I’d wager that it’s only bearable because of its “high risk, high reward.” The risk being hours of discomfort and the reward being what could come from possibly ‘looking better’. In all honesty, I wish I had their discipline.

Ironically, beyond women being predictably time-poor, studies would argue they are also more predictably at risk of pain. And not from the possible hair ties affecting blood flow to their ears.

The gender pain gap is violently real. Approximately half of chronic pain conditions have a higher prevalence in women compared to men. 40 per cent of women are said to be living with chronic pain. And like most things, the gender pain gap is wider for women of colour.

It’s here where the shed routine gains its particularly cruel inflection. The reign of pain is omnipresent in the lives of women, and yet, now it’s being prescribed as necessary even in our times of rest.

Technology and the illusion of time

It feels like for most of the modern era, women have been at the mercy of time. Time lost to the emotional and domestic obligations of wifedom chores, childbearing, caring so much more etc..

When the egg beater was invented, the time spent in the kitchen cooking food by women should have theoretically been reduced. The prep work for the era’s typical meals should suddenly be easier thanks to this new technology. However, food trends would quickly recast angel food cake as the emblem of a good middle-class wife. A food that takes hours of intense cooking, patience and discipline.

The process defines much of women’s lives. As new technology gets created, the expectations of womanhood only seem to get complicated rather than convenient.

The shed routines feel similar to that. As baby botox, filler and other procedures grow more and more common and weight-loss meds grow more accessible, theoretically, it’s become more convenient to maintain societal beauty expectations (emphasis on the theory part of this sentence). But something new is born to make sure that can never be utilised for rest or pleasure.

A snakeoil salesman in a sheet mask

While beauty standards claim us all, it’s the traditionally feminine-looking women who remain most successful at commodifying these maximalist routines into an income stream. The corporation and the individual get muddled by the influencer industry but something sinister emerges at the sight of beautiful young women, chanting unproven benefits and then, directing viewers to shop their affiliate links.

This advice is given through the guise of ‘big sister’ status. The corporate influencer makes her bag through a para-social friendship. It's secrets from a girl who’s seen it all before, but with a link in bio.

We tend to give the individual immunity in all matters of ethics, and direct our gaze to the corporation. But in this case, it’s a brand, embodied via an individual, that gets to rake in thousands of dollars through insecurities. Subverting and reshaping all we’re used to.

It’s a new-wave reflection of when Sandra Lee Bartky said “The disciplinary power that inscribes femininity on the female body in everywhere and it is nowhere, the disciplinarian is everyone and no one in particular.”

And in the case of influencer culture, it’s your wise sage who is also your profiteer. Throw choice feminism into the mix, and your disciplinarian isn’t just your internalised male gaze but you, yourself and your purest desires.

This type of (very relatable) content reveals this tension. The shed routine is not interested in appeasing the immediate male gaze – it’s a total embrace of the unsexy. It’s a refreshing departure from the internalised male gaze that has you performing femininity in the privacy of your home (cue that meme about sleeping with your leg which I cannot find but does exist).

With the shed routine, you have permission to be ‘ugly’ – but only under the pretence that it will eventually make you sexier.

Can I be a bitch for a second?

Sandra Lee Bartky challenged liberal feminism when she said, “We are often told that women dress for other women. There is some truth in this: who but someone engaged in a project similar to my own can appreciate the panache with I bring it off.”

This same idea can be applied to the suggestion that this is done for oneself, and thus, it is vocational. It is undeniably done for oneself – the routine provides a comforting sense of control over the chaos of the patriarchy. But we can admit it’s not ‘done for oneself’ as in, fulfilling a spiritual, emotional need. And that doesn’t make it unimportant or frivolous at all. The things women do to try and starve off annihilation are survival – as are attempts to romanticise those things and reclaim them.

But still, shed routines feel awfully close to negging. Like a practical joke evilly concocted to see how desperately we want it. And I guess, that’s all the rules and disciplines of consumerist femininity because, as Sandra said:

“The disciplinary project of femininity is a “setup”: it requires such radical and extensive measures of bodily transformations that virtually every woman who gives herself to it is destined in some degree to fail.”

Anyway all of this to say, I have a chin strap sitting in Beauty Bay cart.